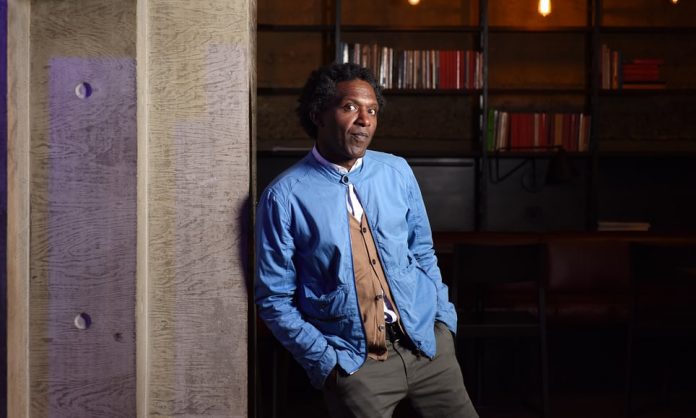

In a blistering one-off show, poet Lemn Sissay heard – for the first time – the record of his suffering as a child in care. He explains why the theatre was the safest place to relive his beatings and betrayal

I have never been in a theatre audience like this one – so loving, supportive, involved. Then again, there has probably never been a production quite like this. It is the ultimate verbatim theatre. What’s more, part of the verbatim is happening live, unscripted, in front of us.

Lemn Sissay’s The Report, at the Royal Court in London, is just that: the reading of – and his reaction to – the psychologist’s report about the abuse he suffered over 18 years as a child in the care system. It is a one-off production. This is, by turns, theatre as shock treatment, theatre as therapy, theatre as protest and, perhaps ultimately, theatre as survival. We come away with a microscopically detailed portrait of the poet – and the system that did its best to destroy him.

Sissay, now 49, was born to an Ethiopian mother in Wigan. She was a young woman – a girl really – who had come to study in Britain and found herself pregnant. She was placed in a mother and baby unit and, at two months old, Sissay was put in care. His mother was asked to sign adoption papers and refused – she wanted her son back when she could manage better. Social services ignored her wishes, telling his long-term foster parents to treat this as adoption. Sissay was renamed Norman by his social worker, who happened to be called Norman.

His foster family were a white working-class couple who had done well for themselves. He was a teacher, she a nurse. They were strict, but they were loving in their own way. At 12, he became difficult, eating cake without permission and staying out late at night. They said the devil had got into him, they couldn’t cope and returned him to social services. They didn’t want to see him again.

Theatre as shock, therapy and survival … Julie Hesmondhalgh and Lemn Sissay in The Report. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi for the Guardian

From the ages of 12 to 18, he went from care home to care home, where he was physically, emotionally and racially abused. Sissay was always told his mother had abandoned him. At the age of 16, he bought tiny tins of Airfix paint in gold, red and green, opened the top window, and painted a bit of the roof in the colours of Ethiopia. For this, he was sent to an assessment unit where most of the children were on remand. He had to be accompanied by a guard to the toilet at night and was strip-searched after friends visited.

When Sissay eventually left care, he was given a flat with no bed. The head of social services ordered that he be sent into the world without a penny, to teach him a lesson, although he was never told what that lesson was. At 18, Sissay asked for his files. He had no family, no photos, no letters – his entire history was contained in these files. He was not given the files, but he was given two pieces of paper that revealed his whole life had been a lie. The first said his name was actually Lemn Sissay. (Lemn means “Why” in Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia.) The second was a letter his mother had written to the social worker when Sissay was one, pleading for his return.

Ever since, Sissay has been trying to reclaim his social services files. They alone contain the truth of his life, or something approximating it. In 2010, he made a radio documentary, Child of the State, in which he returned to Wigan to find the files. Initially, he was told they were now held by the data services company Iron Mountain. At the end, he was told sorry, they are lost.

Two years ago, the head of social services got in touch to say his files had finally been found. And this was the start of the process that has resulted in tonight’s performance. In recent years, Britain’s councils have begun to compensate children who were abused in their care. After Sissay was handed his files, he was told that Wigan council wished to apologise to him.

Sissay is an old friend of mine. He is one of the funniest and warmest people I know, extraordinarily animated with a life-affirming laugh. He is also one of the most damaged people I know, suffering paralysing depression that forces him to withdraw into himself and disappear for months at a time, sometimes longer. The public tends to see more of the first Sissay. But not tonight.

Two days before The Report, we meet to discuss it at King’s Cross station. He is on his way to Carlisle for a gig. Sissay is always on the road, travelling light, with nothing but his words. He says he is in a better place than he has been for years, and it is this that has enabled him to make a compensation claim.

It has been two years since he received an apology from the great and good of Wigan council. “They moved the table to the back of the room, put the chairs in a circle. I was like, ‘What the heck is this?’ I said I wanted an apology on five fronts: you stole my family, you changed my name, you gave me to foster parents that were inadequate, you imprisoned me and I suffered constant racism from the get-go. I was spat at, punched, kicked, throughout my time in care. I was dehumanised.

“They said we apologise on all the points and told me I was entitled to make a claim. I said: ‘I’m not going to discuss money with you. I’m not going to barter my experience with you.’ I said: ‘I’d like your lawyer to talk to my lawyer, and then we’ll be fine.’”

His lawyer, an expert in child abuse, made the claim. Sissay tells me, off the record, the amount: nothing outlandish, in the low six figures. Wigan took six months to respond to him and then offered 11 times less. Sissay says he knows of abuse victims who settled for as little as £2,000. “I was in care for 18 years. The care system should be a place where 18 years is a gift because you’ve got all the resources, the best education, the best psychotherapeutic work, and actually it was 18 years of betrayal, secrets, lies, beatings, incarceration.”

This is the genesis of the Royal Court show. To challenge the compensation offered, victims of abuse have to provide a psychologist’s report detailing what they suffered and how it affected them. “You have to justify why everything that has happened to you has happened to you – and how it has played out in your life. Somebody told me the process of doing the psychologist’s report was worse than the abuse she went through. Part of the reason I’m doing this on stage is to show what people have to go through to get redress.”

There is another reason. Sissay has found it too painful to read all his files, let alone the psychologist’s report. He says he will find it easier in the theatre. “I feel good on stage. I feel, in a bizarre way, like I’m with family. This is the best way for me to look at those files. I couldn’t be in a safer place. I feel more comfortable having this out in the open, because they fucked me up when I was on my own.”

Sissay’s mother, Yemarshet, in 1965. Photograph: Courtesy Lemn Sissay

Sissay and Julie Hesmondhalgh, who plays the psychologist, take to the stage in a minimalist production (two chairs and a table) directed by John McGrath. The performance lasts two hours – Hesmondhalgh reading the report, Sissay listening and occasionally responding. It is blisteringly powerful: the mix of Sissay’s poetic language (much of the time the psychologist is reading out his words) and the clinical analysis of Sissay’s condition.

Hesmondhalgh is wonderful – particularly when she breaks out of character to ask Sissay if he is all right and if it’s OK for her to go on. We listen to her and watch him: tapping his foot, shaking his head or nodding along, sometimes smiling, occasionally laughing (particularly when the psychologist mentions his “avoidance of even trivial exercise”).

This is theatre at its most raw. Sissay might feel he is in a safe place, but at the same time he could not be more exposed, hearing it all for the first time. So we learn about how his foster family eventually rejected him; how he grew up as the only black boy boy in the village and strangers spat on him from buses; how he was named Chalky White in care and beaten by members of staff.

We find out how he started writing poetry for solace, how he spent more than a decade (and all of his money) crisscrossing the world to track down his family, and how one by one they rejected him. We hear about the achievements – the plays, the books, the MBE, beating Peter Mandelson to the chancellorship of the University of Manchester, the two honorary doctorates. Here, in a rare interruption, Sissay kicks at an imaginary football and shouts: “Goaaaaaal!” The audience laugh – with relief.

Most painfully, we learn about the scars on his wrist, the glue he sniffed when he was 12, the way he drank himself into oblivion as an adult (he has been teetotal for three years, apart from one lapse), how he craved intimacy but couldn’t cope with it, the relationships that imploded, his sense of inadequacy, hypersensitivity, extreme shyness, pathological fear of rejection, the birthdays spent alone in tears. We hear the psychologist’s various diagnoses: post-traumatic stress disorder, avoidant personality disorder, alcohol use disorder.

The Report is never more poignant than when the psychologist states: “He meets some of his needs for acceptance and love through the superficial and impersonal relationships he forms through being famous, whereby he interacts with people but at a safe distance.”

The psychologist concludes that Sissay’s “long-term injuries” were caused by his experiences after being taken from his mother and placed in care, and that he is likely to need therapeutic support for the rest of life. The psychologist says the reason it has taken Sissay so long to make a claim is simple – before he received his files and the apology, he did not think he would be believed.

It is a brilliant, draining show. At the end, everybody stands and cheers. You sense they would rather just hug Sissay. Outside, he is having a smoke. His eyes look gone. Audience members tell him that he is a survivor, a hero, a crusader. “Oh dear, I feel as if you all know me now,” he responds. He says he is happy with the report, and glad to have made it public.

Yes, Sissay has done it for himself – but he has also done it for all the victims of the care system who don’t have a public voice. “This is not about me picking the scab. It is about getting redress, navigating my way through this minefield and trying to articulate what was always meant not to be articulated. We were meant to be ashamed of our experiences and not talk about them.”

He mentions a poem he wrote on becoming chancellor of the University of Manchester. Called Inspire and Be Inspired, it contains the lines:

Open all doors.

Open all senses.

Open all defences.

Ask, what were these closed for?

“It’s about opening up all the dark places that have been closed,” says Sissay. “That’s what we’re doing here. We’re digging up the bodies.”

Source: The Guardian